Singleton Pattern: The Most Misunderstood Design Pattern

Introduction

Ah…The infamous Singleton Pattern. This Design Pattern is one of the most controversial Design Patterns. There is one side that loves them because of how easy they make it to grab state and behavior from anywhere in your application. The other side vehemently despises them; arguing that they make your codebase more rigid. This side even goes as far as to call the Singleton Pattern an Anti-Pattern as they are antithetical to the goal of Design Patterns in general which is to solve problems in such a way that makes your application more flexible to change.

In this article, I hope to bridge the gap between these 2 sides as I believe there are common misconceptions with the Singleton Pattern and its original use case. This misconception largely stems from the misuse and misrepresentation of Singletons and as such, the lovers of the Singleton Pattern grossly misuse them, further fueling the hate that comes from the Singleton nay-sayers. I will explain the real purpose of the Singleton Pattern, because I can say with great confidence that whatever you think the point of Singletons are, you are probably wrong.

What Singletons are not

I’ll first get into what Singletons are not. I will just set the record straight now: I have read many different sources on the Singleton Pattern and out of all of those sources only one gets the Singleton Pattern right and one other does a decent job at explaining it but I still have some gripes with. The source that gets it right is the original Design Patterns book by the famous Gang of Four. The other source that does a pretty good job at explaining this is Learning Design Patterns with Unity by Harrison Ferrone, but this is the one I did have a few gripes with (more on that later in this article). All that said, I recommend both books to anyone reading this article especially the later if you are a Unity Developer. But I must say, if you want to look specifically into the Singleton Pattern, the original Design Patterns book is where you MUST go.

Managers

Singletons are not manager objects (Yes, I’m looking at you Unity Devs). You do not need a manager to be a singleton; If you think about what a manager is in the real world, they simply manage a set of related items. Those items can be people within a department at a job as one example, but not all departments at a company have access to that one single manager. No, the only ones who have direct access to a manager are the people directly under the manager and directly above them. The manager is the one that delegates tasks to the individual workers under him.

Managers in the software world often times work similarly to that of a company manager in the real world. The entities that a manager manages don’t necessarily have a direct reference to the manager object (they can; but not always necessary), but manager objects do often delegate tasks to the individual entities or objects that they are responsible for.

This doesn’t mean they ought to be a Singleton. That said, it doesn’t mean that you should never have a singleton manager; but if you do you need to know why you’re doing it.

Just a Single Source of Global State and Behavior

This one’s a bit of a gacha so I will clarify this now: The thing that makes Singletons special is not the fact that they are global and ensure that only one of their instances exist. I find it insane that no one recognizes this; if all I cared about was having a single global entity of state and behavior that cannot be instantiated more than once, I’d just use a static class. Seriously, what is the difference between:

Static Class

and:

Singleton

All of this, just so I can do

All of this, just so I can do MySingleton.Instance.globalState from anywhere in my application as opposed to simply MySystem.globalState using a static class. The only difference as far as I can tell at the surface is the tedium of setting up the Singleton with the private constructor and lazy instantiation (again, this is a gacha. I know the real difference here, but it’s not what you think it is). If all I needed was this for a singleton, then I’d simply use a static class.

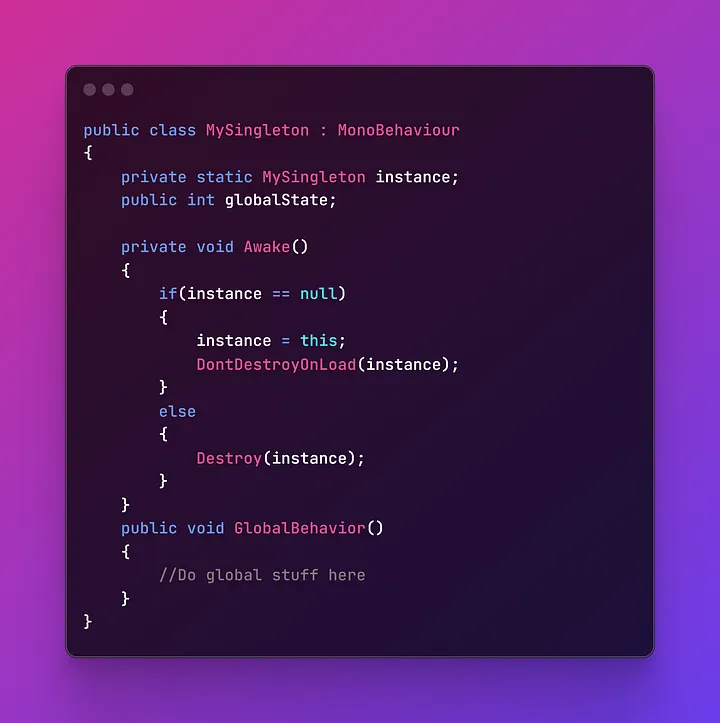

And for Unity folks who prefer the MonoBehaviour version:

Monobehaviour Singleton

Admittedly, you get some extra benefits from doing things this way in Unity because you can serialize fields in a Monobehaviour to give you the drag and drop feature in the editor. And Unity Developers love the Singleton Pattern for this reason, but while this is not necessarily wrong, this purpose for Singletons is generally misguided. There is far more to the Singleton Pattern then just giving you what is effectively a Static class that you can serialize in Unity. If this weren’t the case, then there really wouldn’t be any reason at all to use Singletons outside of Unity; you’d simply use static classes.

Also as an aside, I personally never use Monobehaviour Singletons because they are very messy and very prone to errors because of how Unity GameObject construction works in general. For more information about this I recommend the Unity book on Design Patterns by Harrison Ferrone; he goes through some of the ways you can protect yourself from the common pitfalls of MonoBehaviour-based Singletons. Personally, I just don’t bother with them; I never need the [SerializeField] feature with Singletons. My one gripe with Ferrone’s book specifically on the Singleton Pattern is that he doesn’t get very explicit about what makes Singletons special, and he also doesn’t give proper POCO (Plain Old C# Object) examples of Singletons. But to his credit, he gets a lot closer to the truth on this subject than most other resources I’ve read.

What Makes Singletons so Special?

Ok so if Singletons aren’t what everyone thought they were, then what makes them special? Are Singletons really just glorified Static classes? To answer this question, you need to think about the difference between a static class and a Singleton.

Static Classes vs. Singletons

I’ve already spoken about what makes Static Classes and Singletons similar but to summarize very quickly:

Both Static Classes and Singletons are globally accessible in your application and only one “instance” of them exists at a time during the lifetime of your application.

I use the word “instance” here very loosely since by the technical definition of the term, you can’t instantiate Static classes, but that’s the very point I’m making. When you make a static class, you cannot have an instance of it. Any data or function you create in a static class only exists within the scope of the static class itself and you cannot create another. Effectively, it works just the same as a Singleton.

So what is the difference between a Static class and a Singleton? To answer that let’s take a look at the only source that gets this right, Design Patterns by the GoF:

Use the Singleton pattern when

- there must be exactly one instance of a class, and it must be accessible to clients from a well-known access point.

- when the sole instance should be extensible by subclassing, and clients should be able to use an extended instance without modifying their code.

That 2nd bullet point is Key and almost every source that I’ve read on the subject of Singletons either omits it entirely, or gets it absolutely wrong. What makes Singletons different, is the fact that you can treat it like an object. You cannot inherit from a static class…but you can inherit from a singleton! The Gang of Four clarifies this point further:

Another way to package a singleton’s functionality is to use class operations (that is, static member functions in C++ or class methods in Smalltalk). But both of these language techniques make it hard to change a design to allow more than one instance of a class. Moreover, static member functions in C++ are never virtual, so subclasses can’t override them polymorphically.

What they are referring to are the equivalent of C# static functions. Like I mentioned earlier, you can’t treat static classes polymorphically; you cannot inherit members of a static class. Therefore, if I have a static function in my codebase I can’t override it at all; the term is “static” for a reason after all.

This is where Singletons come in! Since singletons are objects, you can create multiple “kinds” of Singletons in your codebase if you need to. If you have a system that you want to be globally accessible, but you are wary of potential changes to that system, then a good pattern to use is the Singleton pattern.

One Proper way to use a Singleton

I am currently working on a Monster Taming RPG called Creatura. Right now, I’m working on a Skill Tree system for each individual monster in our game and I wasn’t sure how that system might change, I only knew that the system would very likely change, and I needed it to be globally accessible since there will be a few unrelated systems that will make use of it.

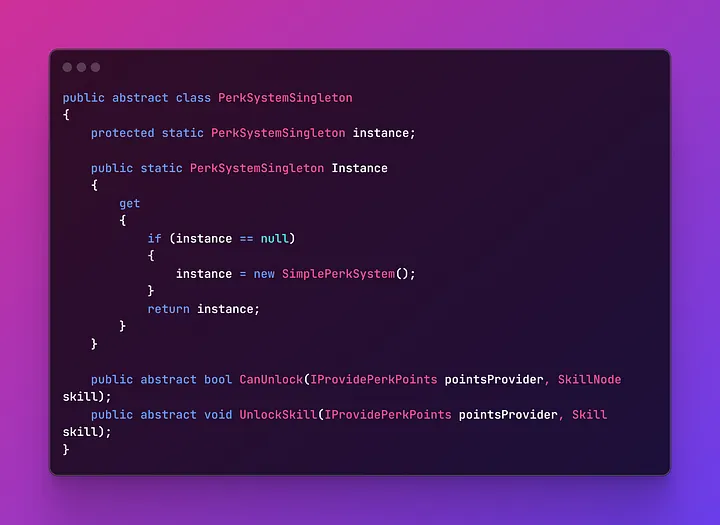

I’ll show you my singleton and then I’ll explain it:

Abstract Singleton Example

I first want to draw attention to the methods I have at the bottom of the codebase. Basically I know that there will be certain conditions for which a monster (or Creatura) can unlock a particular skill in their skill tree. What I don’t know, is how I want it to work specifically. I only know that I want this feature, so I’m deferring the decision to future me by doing things this way.

Notice how the Singleton works more or less the same as any other Singleton would, if you try to get an instance and it’s still null it will create the new instance first and then return it (this is called Lazy Instantiation). If you look, you’ll notice that it instantiates a SimplePerkSystem object. Let’s take a look at that object:

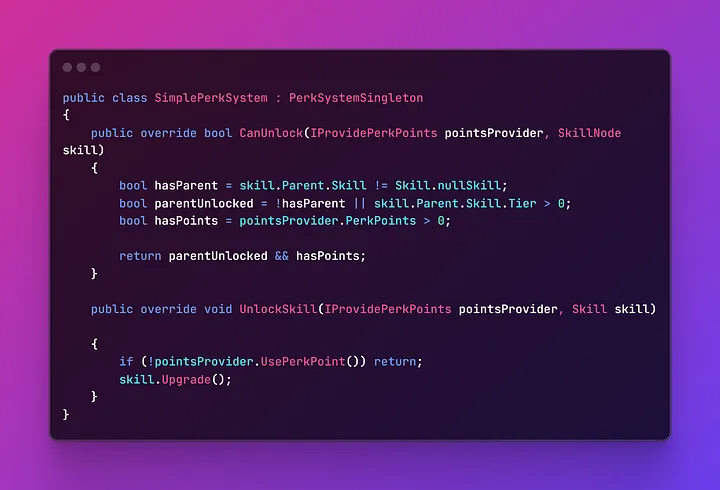

As you can see, this

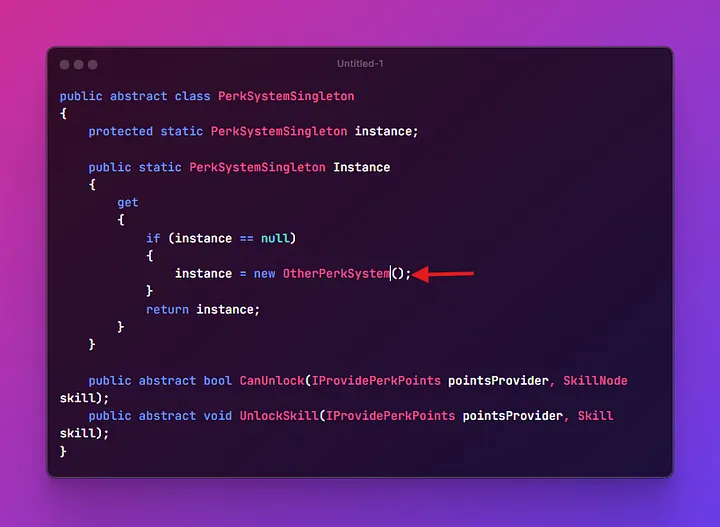

As you can see, this SimplePerkSystem inherits from PerkSystemSingleton which allows me to override the methods of the Singleton. If later I decide I don’t want to handle unlocking a skill a certain way and I need to change it without potentially breaking other systems that use this singleton then all I have to do is write a new class that inherits from PerkSystemSingleton and make sure that the PerkSystemSingleton instantiates the new class instead of the old one:

One little caveat with this is that technically, the concrete subclasses of your abstract singleton classes can be instantiated multiple times. But the idea here is to make sure you only use the abstract Singleton class as the proxy for your global system. You should not be instantiating concrete versions of your singleton from outside the singleton itself.

If you really care about this, you could package up your singleton system in an Assembly Definition and mark your concrete singleton constructors as internal using C#’s internal keyword. But this is a feature specific to C# that doesn’t necessarily exist in other languages.

This is what it looks like to use the Singleton:

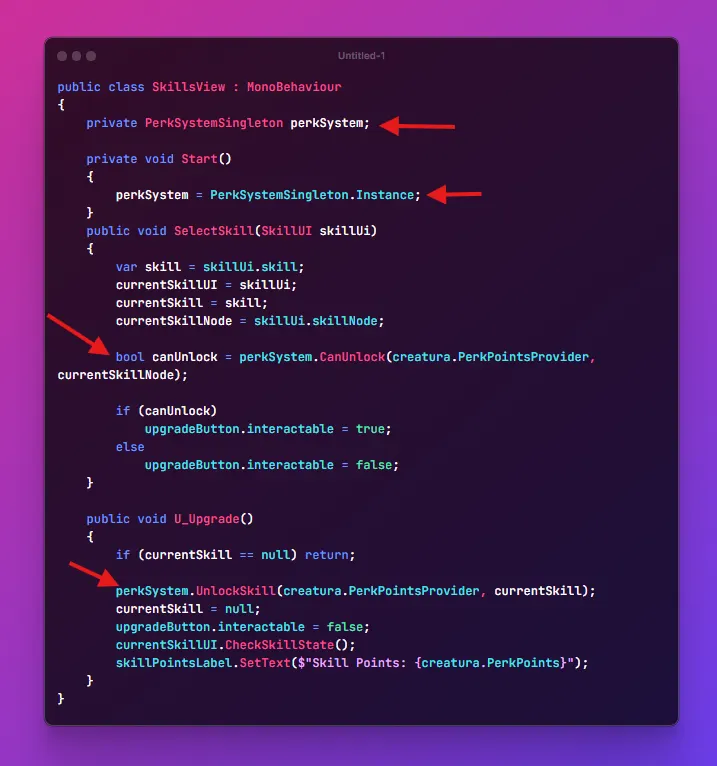

Notice how my client system (

Notice how my client system (SkillsView is an object that handles the UI for a monster’s Skill Tree) doesn’t know anything about any concrete implementation of my PerkSystem Singleton. It only cares about the PerkSystemSingleton object and that object is solely responsible for its own instance. No one else gets to decide which instance that object uses but itself internally. This opens my perk system for extendibility and closes my client SkillsView system to change (following the Open/Close Principle). This also inverts my SkillsView’s dependency from a dependency to a concrete implementation of my Perk System to an Abstraction of my Perk System (following the Dependency Inversion Principle).

Conclusion

To the lovers of the Singleton Pattern, I say that while it’s ok to love the Singleton Pattern, it doesn’t have nearly as many use cases as most proponents tend to think it does. Be careful when using Singletons as they still have a problem with global accessibility in that, it’s very easy to get carried away. If you use singletons, consider the above approach to alleviate the risks of inflexibility in your codebase.

To the haters of the Singleton Pattern, I say that your misgivings of the Singleton Pattern are well placed. Many developers misuse the Singleton Pattern and don’t even know its roots. But this also includes the haters as well; the vast majority of people who hate the Singleton Pattern do so because they misunderstand it. If you read the original GoF book and understand it, then you will fully understand what Singletons are for and will be better equipped to argue for or against them.

As for me and my stance on this pattern, I treat it like any other tool in my toolbox. I use it when I need it and not just because I “like it”. The Singleton Pattern is a Design Pattern you use when you need to marry the rigidity of Static Classes to the flexibility of Objects. If you use Singletons for anything else other than that purpose, you are using them wrong. And if you don’t recognize this purpose then your idea of what a Singleton is, is wrong.